Ora et labora: pray and work.

This was the motto of the medieval monk. This simple phrase moved the life of prayer from the realm of the ascetical heroism of the few to a life that was both accessible to normal Christians and helpful for society. Monks were called to a life of prayer, and pray they did.

But they also worked. They built. They planted. They copied texts by hand. They pastored churches. But in all that work their rhythm of life was set to the meter of daily prayer. Seven times a day, the monks would pray. Their life was one of meditation on God’s wondrous works. Their work flowed out from their prayers and enabled their work to be a vocation, a calling, that was defined by God’s goodness and love for the world, not one motivated by greed, success, pride, or jealousy.

It was not always this way for monks. The ancient monks of the Egyptian desert did not place work as a priority. Their goal was an ascetical ascent to God. Yet the goal of 6th century monastic father Benedict of Nursia was to set prayer and work in harmony. In order to do this he lessened the monastic requirements on prayer to make them more reasonable. He increased the provision for sleep, food, and drink so that the monks could be productive. His goal was not to ascetically bludgeon evil out of the monk, but to set the monk into an ordered life that valued work as an objective good and recognized the necessity of prayer in the life of the worker.

In essence, the daily prayer patterns that Benedict developed for his rule were designed to be a pattern of prayer that the worker could manage. It was intended to be reasonable and doable. It was intended to uplift and encourage, not berate and punish.

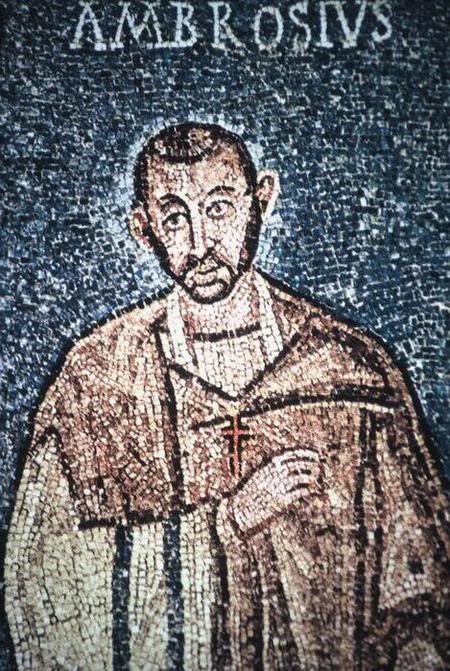

The monk’s life was, as one commentator on The Rule of St. Benedict put it, “an intensely lived Christianity.” Their life was more intense in prayer and in the denial of some worldly goods. Yet the monastic call to prayer was never just for monks, it was for all, even if monks were the only ones ever to fully attain to it. St. Francis, after visiting the Sultan of Egypt remarked at the devotion of Muslim peoples and their commitment to prayer. In a letter to Christian rulers he suggested that cities emulate the Muslim public calls to prayer with a bell or a trumpet or some sort of public audible sign so that Christians everywhere would be called to pray. In the early Church, Hippolytus of Rome encouraged all Christians to pray, at least some kind of prayer, seven times a day according to the Psalmist who wrote, “Seven times a day I praise you for your righteous rules,” (Psalm 119:164).

The Protestant Reformation, one might say, was not an effort to do away with all the emphases of monasticism entirely, but to return the positive aspects of monastic spirituality to all the people. This was in effect to turn the entire Christian church into a monastery, a “School for Christ,” as Benedict of Nursia himself put it, and as Knox notably called Calvin’s Geneva a thousand years later. The Reformation was about returning the spirituality of the Church back to the people. It did not intend to remove anything from the richness of the faith.

The phrase ora et labora, pray and work, shows us the goodness of work. It also communicates the need for prayer. All of us work. We work and work and work. There is no end to our work. But is our work good? Do we have this notion that work is secular and prayer is sacred? Do we drive a hard division in between our work during the week and our prayers on Sunday? The scriptures tell us that our work is good. The Christian faith has not driven such a hard wedge between the sacred and the secular. While prayer is not needed to sanctify work, (work is a created good), returning prayer to work reinforces work’s goodness and helps to push against the forces of this world which seek to turn our work toward evil and unhelpful and unhealthy paths.

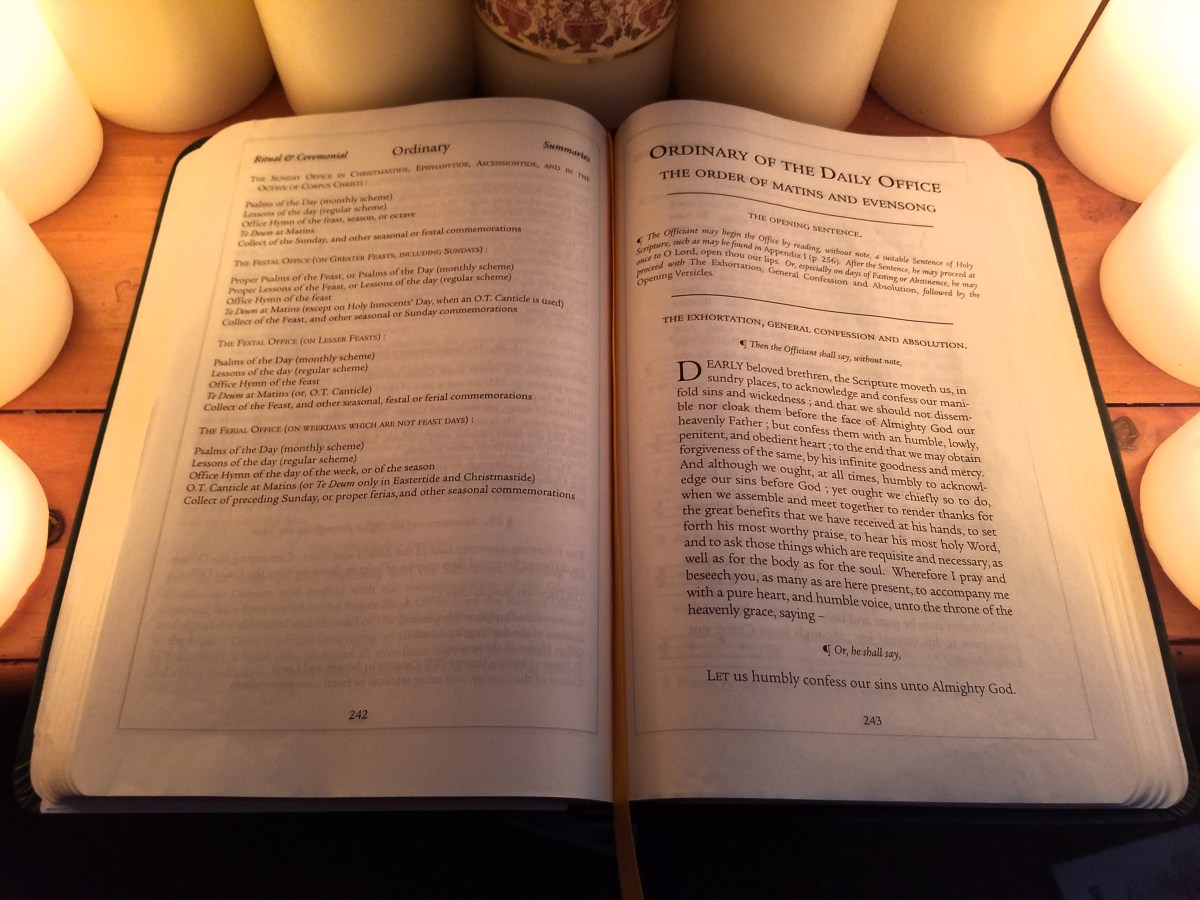

Ora et labora also shows us the need for prayer in our lives. We need to pray. Paul says, “Pray without ceasing.” Yet do any of us really know how to go about doing that? Daily prayer on the pattern of the divine hours gives us a pattern for prayer that we can keep.

Work needs prayer. Prayer needs work. We cannot continue to do our best work unless we stop to fill our tanks with the spiritual fuel of word and prayer. The best work is done from a tank that is filled to the top, a goblet of goodly wine that is full to the brim and overflowing, as David wrote. This is a kind of prayer, you see, not just for the various prayer needs of our lives, but a formative prayer: a prayer that forms, shapes, molds; a prayer that fills us and renews us and restores us. There is room in that prayer for petitioning God according to our needs. But the main force of the daily office is to fill our tanks, to nourish and strengthen us, to make us better Christians out in the working world.

Ora et labora. Pray and work.

This essay originally appeared at Mere Orthodoxy. Please visit their great website.