This is silly. I can’t believe I’m doing this. (So don’t do it, LeCroy.) Sigh. I’m gonna do it.

There’s this song. It’s schmaltzy and sentimental, like many of the contemporary Christian songs I grew up with. If you like this song, I advise you to stop reading. Because I’m going to trash it.

I grew up in the glorious heyday of CCM, and I loved every minute of it. I went to their concerts. I sang their songs in church services and in youth talent competitions. I bought their tapes, read their books, and had their posters on my bedroom wall. Like most Evangelical teen boys growing up in the late 80’s and early 90’s I had a crush on Amy Grant. Later I had one on Rebecca St. James. I listened to the local CCM station non-stop, even as a kid sending in some of my meager dollars for their pledge drive. I’m not really cynical or bitter about it. I am mostly appreciative of such a wholesome upbringing in a non-ironic way. The point is, I’m an insider offering insider critique.

Here’s my critique: “Mary Did You Know?” is a terrible song.

I mean, the tune is catchy enough. It sticks in your head like many of CCM’s greatest hits. There’s nothing like a good spirit-filled musical climax or key change to grease the skids on a flagging worship service (I grew up Pentecostal. Key changes were a means of grace for us. The Spirit seemed to always coincide with the high notes.). Aesthetically, it fits in with the era in which it was written. It’s in the Bill Gaither milieu, so it’s melodically rangy and adeptly uses musical climax to stir the emotions. The original recording was by Michael English in 1991. Michael English is an incredible singer. I saw him live once, because of course I did. You have to give that original a listen. Hoo, boy. It’s fantastic (now I’m being nostalgic and a little bit ironic, but in a good way). The music is Phil Collins and the vocals are Michael McDonald. There’s even a third verse drum entrance crescendo à la “In the Air Tonight.” So, as far as that goes, it’s not bad. In fact if you love 80’s music it’s glorious, if about a decade late as most CCM is.

But the lyrics. Ugh.

The author, Mark Lowry, is a great guy. He’s a comedian and singer who tours with Bill Gaither. But he’s not a biblical scholar or theologian, bless his heart.

I mean, the song is fine. If you like it, listen to it. Like the old adage about wine, if you enjoy it drink it. If you like Boone’s Farm, slurp it up, my friend. No judgment here.

But just so you know: Mary knew.

This is my biggest problem with the song. It’s inaccurate and unhelpful. (But, pastor, I just listen to it because I like the beat). We can go line by line through the song to illustrate this (and don’t worry, I will), but in general it presents a version of femininity in Mary that is not true to her or the other heroines of the Bible. It presents her as a clueless passenger in this journey instead of one of the key players. It woefully downplays the importance of her role. Not only did Mary have the perilous job of carrying the God-Man in her body to full term, consider this: the infant mortality in the Roman Empire was about 30%, and an additional 30% of children did not reach adulthood. That’s only a 40% chance of Jesus living to the age of 20. And that’s not even taking to account the fact that people were out there actively trying to kill him. Powerful people. With armies.

Mary’s job was to feed him, clothe him, and keep him safe. She also taught the young boy manners and took him to church. He learned to speak by imitating her. He had her accent. The Eternal Word of God learned human speech from this marvelous woman by watching her lips and imitating her sounds. And all indications are that she did it for the latter half of his life as a single mother.

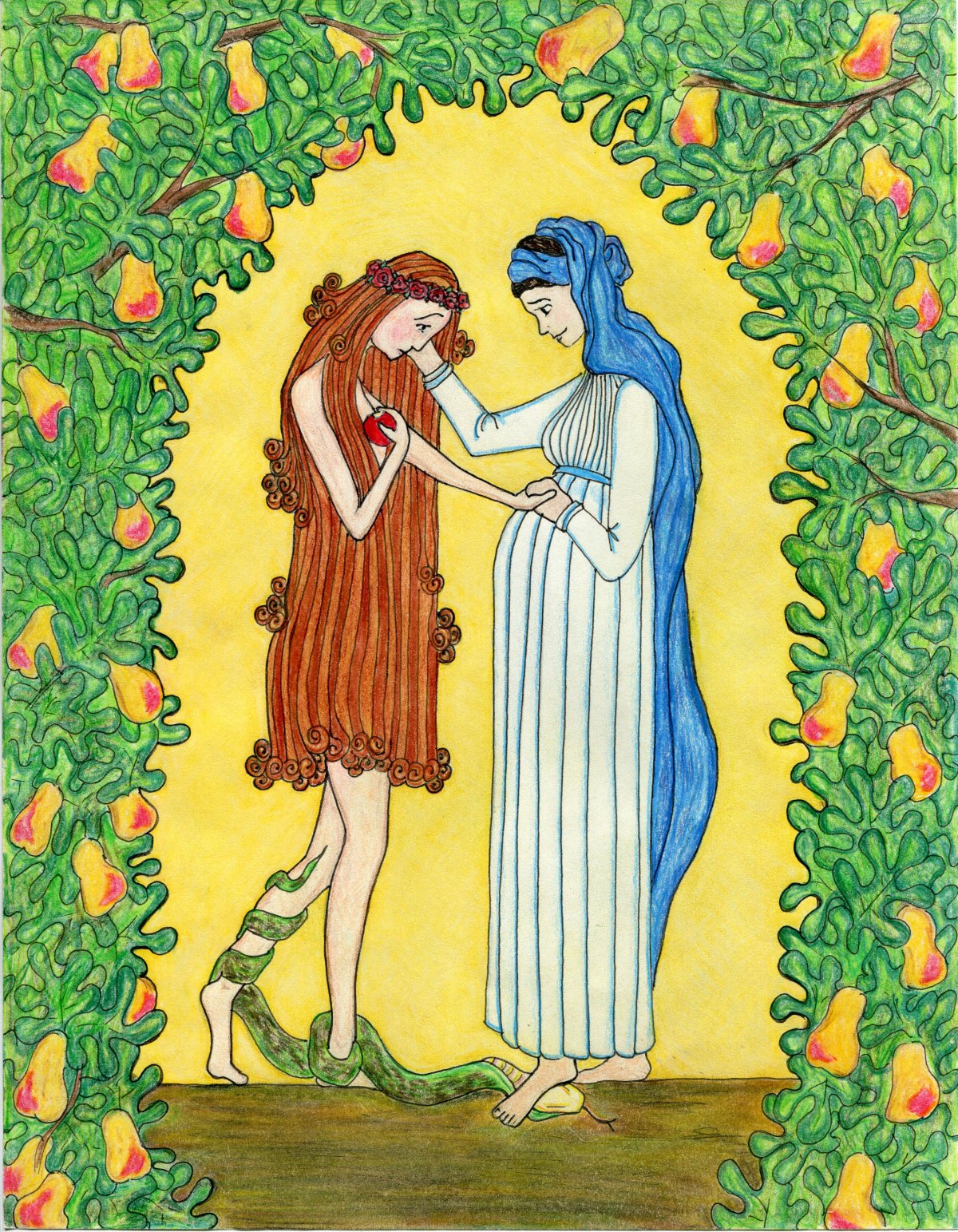

She did all of this while remaining faithful. She did not take the apple, as her mother Eve did. She was graced by God and did not waiver. She wept at the foot of the cross when the Apostles fled in fear. She was in the upper room on Easter evening and on Pentecost. She helped Luke write his Gospel. This was a strong woman, who stands at the pinnacle of all the heroines of the Old Testament. Higher than Deborah. Higher than Jael. She may not have crushed heads with her hands, but she raised the head-crusher par excellence. She was a Miriam (that’s her name, by the way) seeing her baby boy down the Nile to safety and then raising him to be the deliverer of her people. She is a leaping, dancing prophetess, singing on the shore of the Red Sea with the drowned army of the enemy lying submerged within. Only that beachhead was not in Arabia but in the hill country of Judea in response to a leaping, dancing fetus and a blessed declaration by her auntie. Yet the song is just as victorious and prophetic as the song of her namesake centuries before.

She knew.

Let’s put this to rest. The image of Mary as a passive, quiet bystander who just happened to be the human incubator of the most high, praised for her purity and her quiet virtue, is a product of wrongheaded ideas about sex, purity, and the human body which sadly dominated the early church and the middle ages. Mary was not virtuous because she was a virgin. She was a virgin because she was virtuous. And she didn’t stop being virtuous the moment she was no longer a virgin. I almost typed when she lost her virginity, as if virginity is a thing that can be lost and when you lose it you are damaged goods. There are some purity preachers who go about the country giving Christian teen girls shiny brand new pennies and telling them not to lose their virginity because then they will become tarnished. They need to keep their pennies shiny and bright so that they can give that gift to their husbands. What a load of hot steaming garbage! If a girl falls into sexual sin she hasn’t become any more tarnished than she already was, for heaven’s sake. She needs to repent of that sin and endeavor towards chastity in the future, but she isn’t damaged goods. The gift that she will eventually give her husband is not her virginity, but her very self and her promise to be his faithful wedded wife. We need to put this thing to bed for good. By the way, those same preachers don’t give the teen boys shiny pennies. What sexist nonsense!

I digress. Though, the image of Mary as meek and mild does come from that same purity culture. I could give you an in-depth history of the development of sexual purity culture, how it began as a result of the cessation of martyrdom and the rise of the monastic class in the early Middle Ages, but I’ll spare you that. The high-point of this insanity is demonstrated in the medieval idea that when Jesus was born he did not pass through Mary’s vagina, but miraculously passed through her belly, leaving her maidenhead intact. I’m not joking. Here’s the point: Mary’s virginity was not a virtue in and of itself. It was important that she be a virgin in order to serve as a symbol of the new creation and to prove that she conceived by the Holy Spirit. To further demonstrate this, Rahab is a mother of Jesus and she was decidedly not a virgin. Her former life of prostitution did not make her unworthy of mothering Messiah.

Mary was not a hapless damsel in distress, the prototypical medieval maiden cloistered in her embroidery with her ladies-in-waiting. She was a warrior princess. She was Eowyn of Rohan singing and slaying. Her Magnificat, sung on that Judean hillside, was a response to the devil whispering to her, tempting her to the apple saying, “No man can kill me.” That song and her courageous life afterward is her reply, “I am no man.”

She knew. Frankly it is insulting to ask her the question.

Let us analyze the lyrics of this song.

“Mary, did you know that your baby boy would one day walk on water?” Well, no, she wasn’t omniscient, but she did tell the servants at the wedding of Cana, “Do whatever he tells you,” (John 2:5). She knew her boy was a miracle worker.

“Mary, did you know that your baby boy would save our sons and daughters?” Absolutely, unequivocally, yes. She named him “Yahweh Saves.” The angel Gabriel told her to name him that (Luke 1:31). And the same angel told her husband this, “He will save his people from their sins,” (Matt. 1:21). I assume she and Joseph talked. Further, Zechariah, after his son John the Baptist was born, sang, “You have raised up a horn of salvation for us in the house of your servant David,” (Luke 1:69). Old Zech was long gone when Luke wrote his gospel. Who opened up the family photo album for him? It was Mary. She is the source for the material in the first two chapters of Luke. She knew.

“Did you know that your baby boy has come to make you new?” Yes, see above.

“This Child that you delivered will soon deliver you?” Yes. She literally named him “Deliverance.” Again, see above. Though I will grant that this is some nice word play.

“Mary, did you know that your baby boy will give sight to a blind man?” Yes, see Isaiah 28:19, Isaiah 61:1, Luke 4:18, and Matthew 11:5. Also see above that she knew he could work miracles.

“Mary, did you know that your baby boy would calm a storm with His hand?” Again, she was not omniscient, but she knew he would have power over nature as the divine Son of God. Gabriel told her that she would be impregnated by the Holy Spirit and that she would give birth to the Son of the Most High. Again, due to the evidence in John 2, apparently, she understood that meant that he had divine power. Elijah and Elisha demonstrated power over nature, so it’s no stretch to think that Jesus would. Plus, Gabriel told Mary and Joseph that he would be called Immanuel, God with us. She knew.

“Did you know that your baby boy has walked where angels trod?” Well, technically, he hadn’t done that. He didn’t have legs until he was born. Did she know he was a pre-existent deity? See above.

“And when you kiss your little baby you’ve kissed the face of God?” Ok, here’s the only one where I admit she probably didn’t know this. But maybe she did. All the evidence was there. I wouldn’t be surprised if she did know this. Gabriel did tell them to call him Immanuel, after all.

“Mary, did you know? The blind will see, the deaf will hear, The dead will live again, The lame will leap, the dumb will speak The praises of the Lamb!” Yes. Read the Old Testament prophecies about Messiah. They predict all these things.

“Mary, did you know that your baby boy is Lord of all creation?” I think she knew this. He was the Son of the Most High God that would rule over an everlasting kingdom (Luke 1:32-33). She knew he was Messiah and she knew all the glorious things described in Isaiah that Messiah would do. Psalm 110 depicts a Messiah who is the dread judge and ruler of all. She knew that he possessed divinity as the Son of the Most High. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that she knew that he would be Lord over the entire creation.

“Mary, did you know that your baby boy will one day rule the nations?” Absolutely she knew this. Gabriel told her so, and see everything listed above. Also, take into account the Song of Simeon who declared that he was to be a “light to the nations,” (Luke 2:32).

“Did you know that your baby boy was Heaven’s perfect Lamb?” OK, this is a good question. Did Mary know that Jesus was the agnus Dei? I think so. She knew that he was going to save his people from their sins. As a well-educated Israelite she would know the only way that could happen was through sacrifice. Further, when John the Baptist came on the scene, the first thing he said about Jesus is that he is the Lamb of God who will take away the sins of the world (John 1:29). How did he know that? Was it because the Spirit shot him through with an on-the-spot revelation? Or was this a well-known fact in the family from the time of Mary’s visit, Elizabeth’s declarations about Mary and Jesus, and Zechariah’s song? I think she knew.

“And the sleeping Child you’re holding is the great, the Great I AM?” See above. But here’s one more piece of evidence. When Mary visited Elizabeth, Luke records that the baby, John, leapt in her womb and she was filled with the Holy Spirit and started prophesying. The text says she then started singing. What was her song? “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb! And why is this granted to me that the mother of my Lord should come to me? For behold, when the sound of your greeting came to my ears, the baby in my womb leaped for joy. And blessed is she who believed that there would be a fulfillment of what was spoken to her from the Lord,” (Lk. 1:42-45). The mother of “my Lord,” she sang. Is that Lord like Master or Lord as a substitute for the word Yahweh? We can’t be sure that they understand it in the latter sense, but it’s certainly possible that they did.

“Oh, Mary, Mary, did you know?”

Oh, yes, yes, she did know.

Let us not forget the conclusion Luke leaves us with after relaying the Marian material to us in his first two chapters, “And his mother treasured up all these things in her heart,” (Lk. 2:51). Mary was not only the mother of Jesus, but she was his first disciple, as she replied to Gabriel, “Behold, I am the servant of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word,” (Lk. 1:38). She was a student of her son. She treasured these things in her heart and pondered their meaning. During those long nights of feeding him, of rocking him back to sleep when he woke up crying, she pondered the deeper meaning of these things as she poured over the Old Testament scriptures in her mind. Perhaps this is what gave her the resolve to stay faithful when others failed. When the apostles fled and Peter denied him thrice, she was there at the cross, remaining with him till the bitter end. She was there at the tomb on Easter morning. She was there in the upper room at Pentecost. What gave her that faith, that strength, that resolve when others doubted, disbelieved, denied, and fled?

She knew.

Image: Virgin Mary and Eve, Crayon and pencil drawing by Sr Grace Remington, OCSO, © 2005, Sisters of the Mississippi Abbey. Printed versions of this incredible image can be purchased here.