This question came to me from a parishioner: “In the Lord’s Prayer, why do we say, ‘For thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever,’ if it is not in the Bible?”

I thought it was such a good question, I wanted to share my answer here for everyone’s benefit.

There are basically two issues at play. One is pretty simple and the other is a little more complicated.

First the simple one. Though our modern bibles tend to omit the phrase, “For thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever,” it has a very long history of being used in worship in the church. For example, the Didache is a Christian text written in the first century AD (around the year 90AD) shortly after the Bible itself was completed. Didache has quite a bit in it about worship, and it text has the long ending of the Lord’s Prayer in it. So we know that this line was used in worship from the earliest times.

Also, there is certainly nothing wrong with the phrase. The words themselves come from 1 Chronicles 29:11-13:

Yours, O LORD, is the greatness and the power and the glory and the victory and the majesty, for all that is in the heavens and in the earth is yours. Yours is the kingdom, O LORD, and you are exalted as head above all. 12 Both riches and honor come from you, and you rule over all. In your hand are power and might, and in your hand it is to make great and to give strength to all. 13 And now we thank you, our God, and praise your glorious name. (1 Chronicles 29:11-13 ESV)

So, there’s certainly nothing wrong with praying this part of the prayer. It is theologically sound and it is biblical. Furthermore, it has a long tradition in the worship of the church (as long as can possibly be).

So, what is the conclusion? It is fine to pray this part of the prayer and it is also fine not to. It is simply a matter of choice. The one who does not pray it is fine not to do so, and the one who prays it is likewise fine. This is what we call in theological discussions a matter of adiaphora, which is Greek for a choice which is left to one’s discretion.

Now to the second, more complicated, issue. This part of the discussion involves the history of the texts of the Bible as well as the history of the Protestant Reformation.

You ask, “Why do we pray [it] when it is not in the Bible?” Well, the fact that this is not in the Bible is not certain. This is a matter of debate among biblical scholars. Granted most biblical scholars will say that it is not original to the text of Matthew. But this is a guess on their part. A very educated guess based on solid scholarship, yet a guess nonetheless.

You see, the text of the New Testament you hold in your hand is based on two different families of manuscripts. One family is called the Alexandrian and the other the Byzantine. On 99% of New Testament these two families agree. Yet they differ on some points. The ending of the Lord’s Prayer is one of them.

First let me tell you about these two families of texts. By far, most of the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament that we (and by “we” I mean the scholarly community) have are of the Byzantine family. The oldest of the Byzantine texts dates back to the 4th century. That’s about as far back as we go with complete texts of the Bible. The Byzantine family is also the basis for the text used in the King James Bible.

Then we have the Alexandrian family. There are far fewer texts of the Alexandrian family and they weren’t discovered until the 19th century or so (when I say discovered, I mean that Western scholars didn’t know about them). Biblical scholars like the texts of the Alexandrian family because they are cleaner (meaning there are fewer variations between them) and they omit some of these section of the bible (like the ending of the Lord’s Prayer and the long ending of Mark). For biblical scholars, shorter = simpler = less contaminated = closer to the original. Almost always when the Byzantine differs from the Alexandrian, biblical scholars will go with the Alexandrian. This is a generalization, but it is normally the case.

So the New Testament you hold in your hand is mostly of the Alexandrian family, while the King James is of the Byzantine. Thus there are the differences.

Now for the Church history part (if you are still with me I commend you!). The Greek version of the New Testament was not copied very much in the West (by “West” I mean Europe, for the most part), because the Western Church relied on the Latin Vulgate as their main biblical translation. St. Jerome translated the Bible from the original Hebrew and Greek in the 4th century. Jerome was an excellent scholar, and his translation is pretty good, as long as you can read Latin.

The Reformers understood that most people couldn’t read Latin and their emphasis was to get the Bible into the language of the people. Some of the earlier (before the Reformation) translations of the Bible, into English for example, were done from the Latin Vulgate, which isn’t a horrible thing, but it is one step removed from the original.

At the time of the Reformation there was a parallel academic movement called “humanism” and one of the tenets of humanism was ad fontes, which means “return to the source.” Thus the humanists, whether they were Protestant or Roman Catholic, were seeking to produce a text of the Bible in the original languages of Hebrew and Greek. Erasmus was one of these humanists who became a Roman Catholic. Luther was another who, of course, became Protestant.

In search of Greek texts of the New Testament the humanists were forced to go to the Byzantine family, because it was all they could find. Thus the earliest modern versions of the Greek New Testament were of this Byzantine type and subsequently the English translations coming out of the Reformation were also of Byzantine type. As a result, they all uniformly included the long ending of the Lord’s Prayer.

We also have to appreciate the church politics going on here. The Roman Catholic worship service did not include the long ending of the prayer. Imagine when the Protestant Reformers discovered that the exclusion of the long ending in the Roman version of the Prayer was not biblical! They certainly were going to include that version of the prayer in their Reformed worship services, now weren’t they?

Also these Byzantine texts were coming from the Greek Orthodox Church. That’s because they continue to use the Greek text of the New Testament as their Bible to this day. The Reformers had some affinity to the Greek Church because, well, they weren’t Roman Catholic. Furthermore, the Greek Church represented a church that was every bit as old as the Roman Church and was at odds with the Roman Church just like they were. So you can imagine why the Protestant Reformers would have some reason to side with the Greeks on this issue. If you read any writings from the Reformation era you will see how bitterly at odds they were with each other.

So, as a matter of liturgical history, the long ending of the prayer was not used in Roman Catholic services but it was in Protestant ones. This is still mostly true to this day.

Fast forward to the 19th century. In the 19th century Western scholars discovered some biblical texts that were different from the texts they were used to. They began to see similarities between these newly discovered texts and saw that they formed a family of texts. This is when they began to call one family Alexandrian (because it comes from Egypt) and the other Byzantine (because it comes from Greece).

Now the picture of the history of the Bible became a little clearer. What seems to have happened with the Lord’s Prayer is that in the Greek East the longer ending was added to the prayer. This did not happen in the Western churches because Jerome (who was based out of the Middle East) likely used an Alexandrian text type for his translation into the Latin. So we have two strands of liturgical history: the Western churches not using the long ending, but the Eastern churches do use it. Thus we see that at a very early date (as far back as we can go) the Byzantine texts have the long ending, but the Alexandrian texts do not.

But who is to say if the Byzantine ones added it, or the Alexandrian ones somehow lost it? Who’s to say that there weren’t two copies of Matthew circulating? Who’s to say which one is correct? We are supposed to confess and believe that the academicians hold the key to the truth on this matter. Yet their own method directly privileges one textual tradition, the Alexandrian, over another and almost always goes with the shorter reading (which almost always is the Alexandrian). They say, and this is not a bad argument, that textual corruptions naturally enter into a text over time. Thus the Byzantine text has more corruptions. Yet because the Alexandrian texts were hermetically sealed in a vacuum they were free from corruption for something like 1,500 years. Think of the woolly mammoth frozen in ice. You can see why they prefer the Alexandrian if this narrative is true.

At first glance this sounds good. Yet what are we to do with the church for 1,500 years that had this particular “corrupted” Byzantine text? Was the Spirit absent with the church during this time? It is a complicated question.

In my Bible (an ESV) the footnote says, “Some manuscripts add For yours is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever. Amen.” And in the study note (it is the ESV Study Bible) it says, “This is evidently a later scribal addition, since the most reliable and oldest Greek manuscripts all lack these words, which is why these words are omitted from most modern translations,” (emphasis added).

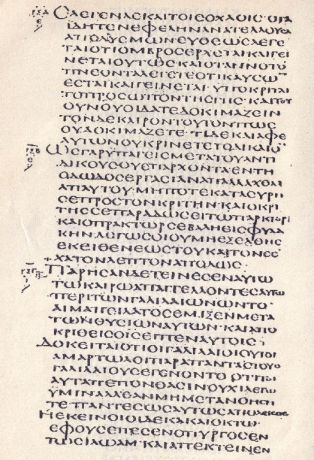

Now, I think I take issue with that. The oldest? Well, technically maybe. The two oldest and best (and by best here I mean complete) examples of the Alexandrian tradition, the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Vaticanus, both date to the 4th century. The oldest and best examples of the Byzantine, the Codex Alexandrinus and Codex Washintonianus, date to, wait for it… the 4th or 5th century. Oldest? Not by much.

What about “most reliable”? That’s a judgment based on the “hermetically sealed” and “shorter = better” parts we were talking about above. Yet if both the Alexandrian and the Byzantine were circulating at the same time from the earliest of dates 300s-400s (Which is, by the way, when the making of books as opposed to papyrus scrolls became more of the norm. Codex is another word for a book.) who’s to say which is better? What about the argument that the text that “won” should be privileged in a reading like this? There’s no debating that up until 100 years ago the Byzantine text had won, at least among those who actually spoke Greek. The Alexandrian text had for all intents and purposes disappeared and was not a version of the Bible that was actively being used. It was a museum artifact. We have to ask ourselves why the Byzantine came to be privileged over the Alexandrian. What was the role of the Spirit in all of this? Again, complicated questions.

So, you see, the “fact” that this is not in the Bible is not a certainty. It has been in the Bible in the East for 2,000 years. It was not a part of the Bible in the Latin West for 2,000 years. It has been in the Bible for the Protestant West for 500 years. It has recently been again removed from the Bible in the Protestant West.

Back to my point on adiaphora. Whether or not this is in the Bible, it is certainly fine to say it. It is a Protestant tradition to say it, and this tradition connects with the oldest traditions of the Church.

My preference is to say it because it is the more catholic (universal) thing to do, in other words, more Christians over the scope of Christian history, and even today, have said it, so I’ll go with saying it.

But if the church across the street does not say it, it’s OK too. It’s not something to worry a whole lot about, in my opinion.

I bet that was a whole lot more than you ever figured you would get out of that question!